CONNECTING CORRIDORS

TARGETED CO-OP FORMATION LEVERAGING LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY

PHOTO: RUSSELL ADDISSON

hAWKINSVILLE QDM CO-OP / GEORGIA

"This is the key to landscape conservation, and the crux of the landscape conservation problem we face across the world – achieving private landowner buy-in to manage in connected modus for the benefit of ALL wildlife."

HUNTER PRUITT - CO-OP SPECIALIST / GEORGIA

By: Hunter Pruitt, Cooperative Specialist / Georgia

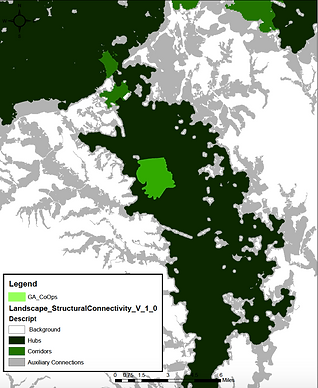

The co-ops in this research were formed organically across the landscape through voluntary deer management partnerships by local landowners. The overwhelming correlation of co-op location to these high-priority conservation corridors highlight how co-ops can be used to maintain and increase landscape and habitat connectivity of wildlife habitat along naturally established corridors. In Figure 1. you can see the location of six Georgia deer management co-ops and their relation to the LCC habitat conservation importance plan from 2018. Actively targeting landowners for future co-op formation along these corridors, where current co-ops have been successful due to a myriad of factors is one such way co-ops can aid conservation planners. In most cases, land-use patterns and topography/hydrology effect possible land-use for development and agriculture. In this way, conservation agencies can effectively focus efforts on co-op recruitment on known habitat hubs and corridors to meet their national or local conservation goals.

The LCC plans provide layers for a variety of non-game and game species conservation priority layers - as seen below. Cooperatives do not only provide a means of achieving wildlife management goals for sportsmen and women, but they provide a tangible plan to address landscape-level habitat fragmentation involving private landowners. By capitalizing on private landowner goals of game management, planned conservation co-ops in high biodiversity regions can be conserved in a more connected fashion. In the below examples (Figure 2-4), we highlight three different ways that co-ops can aid landscape conservation. In Figure 2, we see a 23,000-acre co-op linking a landscape conservation hub with a corridor, while also forming a new corridor to auxiliary connections. In Figure 3, we see a 3,000-acre co-op located entirely within a landscape hub, solidifying the connectivity of this important landscape feature into the future. Figure 4 shows a 5,500 acre co-op located directly on a major corridor linking multiple habitat hubs. These three co-ops highlight the impact that landowner connections can have on national conservation efforts along known wildlife conservation corridors. This is the key to landscape conservation, and the crux of the landscape conservation problem we face across the world – achieving private landowner buy-in to manage in connected modus for the benefit of wildlife.

If you ask any wildlife biologist - worth one's salt - what the biggest challenge facing wildlife conservation around the world they resoundingly agree: habitat loss due to land-use changes and a rapidly expanding human population. The United States is not alone in this phenomenon, as the number one threat to biodiversity worldwide is habitat loss and its subsequent reduction in connectivity and habitat availability for many wildlife species. To understand what connectivity is, how it affects both game and non-game species alike, and how co-ops play a role in combating habitat loss and reduced connectivity we dive deeper into the landscape ecology of private landowner co-ops.

Habitat connectivity is defined as the degree to which the landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement or other ecological processes. Thus, greater habitat connectivity enables wildlife to travel between habitat patches with more ease, while reduced habitat connectivity indicates impediments to wildlife travel that can be quite hard to cross. Reductions in habitat connectivity can result in a decreased ability for biological functions to occur like migration, breeding season movements, increased mortality due to human/wildlife interactions, and decreased health. In most cases, these barriers to movement result in habitat gaps and long-term decreased landscape health.

Today, landscapes that remain relatively untouched with few barriers to wildlife movement are either in remote places of the world with harsh climates, areas that see regular flooding along rivers and shorelines, lands that are arid deserts, swamps that hold water continuously like the Everglades, or topography that makes human development arduous and costly as we see in the Appalachian or Rocky Mountain ranges of the continental U.S. The paradox conservation planners discover is that less temperate climates - usually set aside as national wildlife lands - are on average lower in biodiversity per square mile. Biodiversity is the measure of number of different species and their evenness as a percentage of the present species. In temperate and tropical climates around the world, we see elevated wildlife biodiversity. Across much of the world – and the US in particular – temperate climates are dominated by private lands and landowners. Contrary to this, most of the public land within the U.S is located in areas with reduced biodiversity from a sheer quantitative standpoint. This paradox is what conservation planners around the world face as they plan for the future of landscape conservation, and where private landowner wildlife cooperatives play a key role!

PIECES in THE LANDSCApe equation

Private landowner cooperatives – in this case deer management cooperatives – are formed with like-minded landowners for deer management purposes. As a by-product of this formation, we have larger swathes of the landscape being conserved while managed actively with the same wildlife goal in mind. These properties are connected together through like-minded wildlife management that can be located (and even planned) on wildlife corridors important to state and federal conservation efforts. While completing my master’s thesis detailing deer management co-ops across the United States, my advisor and I realized that the location of co-ops functioning on the landscape were located in high biodiversity areas along corridors of prominent rivers and watersheds within the state. These areas had been previously identified as “high and medium priority” areas within the national landscape conservation cooperative (LCC) plan by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

HAWKINSVILLE qdm co-op / GEORGIA

Figure 1. Georgia Deer Management Cooperatives and their relative location in proximity to the USFWS South Atlantic LCC Blueprint.

FIGURE 2. A 23,000-acre co-op connecting a hub to an important landscape corridor.

figure 3. a 3,000-acre co-op located within a large hub within the south atlantic llc

FIGURE 4. A 5,500-ACRE CO-OP LOCATED ON A MAJOR CORRIDOR CONNECTING HUBS.

About the Author

Hunter Pruitt, Cooperative Specialist / Georgia

Hunter grew up in Georgia, where he started his first QDM co-op when he was 12. He worked for the QDMA for 5 years while attending the University of Georgia (UGA) to obtain his undergrad and graduate degrees in Wildlife Sciences. His masters research was the first to look at wildlife cooperatives on a national scale, and quantify the landscape-level benefits of deer management cooperatives. Hunter help spearhead the National Wildlife Cooperative as a project to quantify wildlife co-ops across the U.S. and provide co-op members with a national voice.